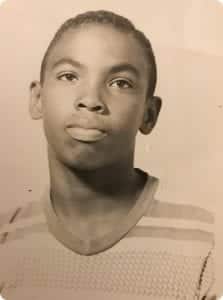

All of us have experiences early in life that, although seemingly insignificant, make an indelible imprint on our psyches - Morrison Warren

As an African-American kid in Phoenix in the 1950s, he always sat in the balcony during his weekly outings to see Lew King Rangers at the local theater. But one week his grandmother, who was of Mexican descent, took him to the movies and insisted they sit on the main floor.

Shortly after Warren sat down, the Anglo girl he sat next to without notice got up and switched seats with her date. That small act had a monumental impact on him.

“Up to that point, I thought I was pretty good. I made straight A’s in school, was good in sports and was the favorite kid in my class,” he recalls. “But that incident, in a little way, hurt me so much that for the rest of my life I’ve always sat on the end seat so you don’t have to sit next to me.”

Not long after that scarring experience, something else happened that would alter Warren’s life in a positive way. A man who worked for the Valley of the Sun YMCA suggested to Warren’s father, a school teacher, that he send his young son to Camp Sky-Y.

“I had never heard of Sky-Y Camp,” says Warren. “At that time, you could sell soap to earn money to pay for camp. I remember selling about $30 of Cashmere Bouquet soap and being so proud I made enough money to go.”

A FEELING OF BEING WELCOME

What stands out most in Warren’s memories of Camp Sky-Y is that he didn’t stand out, even though he was one of only five African-American campers that session.

“When I got off the bus I felt just as welcome and secure as anybody,” he recalls. “The environment was very open, very receptive. We had fun, we ran around. We would go horseback riding, go swimming, go on hikes. When we went to eat, nobody said, ‘People of color sit over there and eat.’”

Warren says in addition to having fun and feeling welcome at camp, he learned a number of lessons that have stuck with him and influenced his behavior. In fact, he credits Camp Sky-Y with changing the course his life may have taken after that incident in the movie theater.

“Of all the experiences I’ve had in life, Sky-Y Camp as much as anything reinforced in me several things,” recounts Warren. “Play fair. People count. Do your best. Give more than you take. If you’re on top, empathize with those on the bottom.”

He lived those lessons as the first African-American athlete ever recruited to play football at Stanford University. He continued to live them when he served as a Marine Corps officer in Vietnam. And he lived them throughout a 42-year career in management at Chase Bank.

“If I would have had a bad experience at Sky-Y Camp, I wouldn’t be the same,” Warren says. “That was a critical point in my life because when I went was right after that girl switched seats on me. But camp was a loving, open environment. Every day, there was a feeling of being welcome. It just set a tone for my life.

“Ever since I went to Sky-Y Camp, I’ve always looked for the best in human beings,” he says. “If everybody went to Sky-Y Camp and heard and felt the inclusive message I heard and tried to live that message, I think the world would be way better off.”